Media and Other Publications in China

When the Democracy Movement began in autumn 1978 with critical wall posters and journals and the activities of independent artists and poets, you would not find a single line on these events in the "official" Chinese news media (such as the central Communist Party organ People's Daily or the big regional papers). Every newspaper and every magazine at that time, was controlled by the CCP Propaganda Department or by one of the "mass organizations" such as the Communist Youth League or the official writers' or artists' associations.

Similar to a practice of other communist countries, in addition to the publically available media, China also had (and still has) a complicated system of "internal" (neibu 内部) publications accessible to a smaller or larger group of selected cadres or otherwise qualified readers. In such publications one did find reports on the activities of the "Beijing Spring" and criticism of the official policies or even high-ranking personalities. The scope of such reporting depended on the designated group of readers, the highest state and party leaders had of course access to more information than medium level cadres.

On such printed materials, the degree of confidentiality was usually mentioned at the top of the first page, it could range from "Internal publication - keep with care" (for publications with larger circulation) to "secret" (jimi 机密) or "top secret" (juemi 绝密), which made it sometimes difficult to distinguish between "media" (usually appearing in regular intervals) or (irregular) documents for internal communication between party and government institutions.

The largest of these internal publications used to be the "Reference News" (Cankao Xiaoxi 参考消息), a daily tabloid with a circulation of 10 million that contained (heavily shortened and edited) excerpts from international media. Cadres, party members and other interested persons were allowed to subscribe to this publication, but the needed a letter of recommendation from their work place or institution, which was easily obtained. Foreigners though were explicitly excluded from reading this paper. Today "Reference News" is freely sold to everyone at the newsstands.

The "Reference News" occasionally also reprinted parts of international media reports that mentioned critical posters, the Democracy Wall or the Chinese Democracy Movement. And they carried regularly more or less detailed references to the Eastern European dissident movements (in China usually interpreted as an opposition against Soviet "Social Imperialism"). Therefore the independent Polish "Solidarity" union or the Czechoslovak "Charta77" have become well-known in China.

From the very few copies of more restrictive internal media available abroad (such as a few issues from the "Situation Summary" from 1978 or one confidential issue from 1980 of "On the Youth Movement" published by the "Chinese Youth Daily"), it becomes clear that high-ranking cadres must have been quite well-informed about the Democracy Movement. Sometimes one would even think that such publications - despite their critical tone - tried to support the reformist faction of the Communist Party by deliberately reporting in detail on dissident movements and their ideas.

"The New Class" by the Yougoslav dissident Milovan Djilas (1957) published by the "World Knowledge Publishing House" (Shijie Zhishi Chubanshe 世界知识出版社, 1963) in Beijing. On the cover it says "For internal use only", further emphasized by a red handstamp that translates "Internal reading".

The same publishing house issued in April 1980 an "internal" translation of the book "Frost from the Kremlin" by former Czechoslovak Communist Party Secretary Zdeněk Mlynář on his ideas for a "humane socialism".

Besides the restricted newspapers and journals there are also "internal" books that can only be bought and read by a selected readership. All big bookstores in China have some secluded shelves (sometimes a seperate room) with "neibu" publications. When customers want to enter and purchase one of these books, they have to show an authorization letter or present an ID card of their workplace to prove their rank in the cadre hierarchy.

During the interviews, several Beijing Spring activists mentioned that they had been able to read publications by Eastern European dissidents translated into Chinese, and that these books have certainly influenced the Chinese civic rights movement. Besides the famous book by Milovan Djilas, a former Yugoslav communist politician, becoming an opponent of the regime ("The New Class: An Analysis of the Communist System"), they also mention works by the Soviet author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, human rights activists Roy and Zhores Medvedev and the Czechoslovak reform economist Ota Šik ("The Third Way. Marxist-Leninist Theory & Modern Industrial Society"). Another stunning criticism of traditional communism was "Night Frost in Prague: The Road to Humane Socialism" by Zdeněk Mlynář, Communist Party Secretary at the time of the "Prague Spring". The title of the Chinese language edition translates (like the Czech original) "Frost from the Kremlin".

The official and generally available newspapers and magazines like the "Peoples Daily" (Renmin Ribao 人民日报) only mention critical wall posters and the Democracy Movement during a short period of time when "paramount leader" Deng Xiaoping (formally "only" Deputy Prime Minister and Vice-Chairman of the Party), had spoken positively about dazibaos and debates in talks with foreign visitors in November 1978.

Also in the course of the rehabilitation and liberation of the Li Yizhe Group in early 1979 in Guangzhou, some party media presented their ideas of socialist democracy and legality in a positive light, including their criticism of the excesses of the Cultural Revolution and the Mao era.

After Deng Xiaoping's speach on the "Four Basic Principles" in March 1979, regular Chinese media would hardly at all touch upon the Democracy Movement, and if so, only in a critical and negative context. Hence the arrests of activists are occasionally mentioned in the press, as well as the trials and verdicts against Fu Yuehua and Wei Jingsheng. The newspapers also report on decrees by the authorities regulating and banning big-character posters and other activities criticizing the regime, not too much in detail though, probably because of the fear that the measures could stir up more debates and negative reactions from part of the population.

Later on, the election campaigns at several universities in November 1980 are not mentioned or discussed any more in the official media.

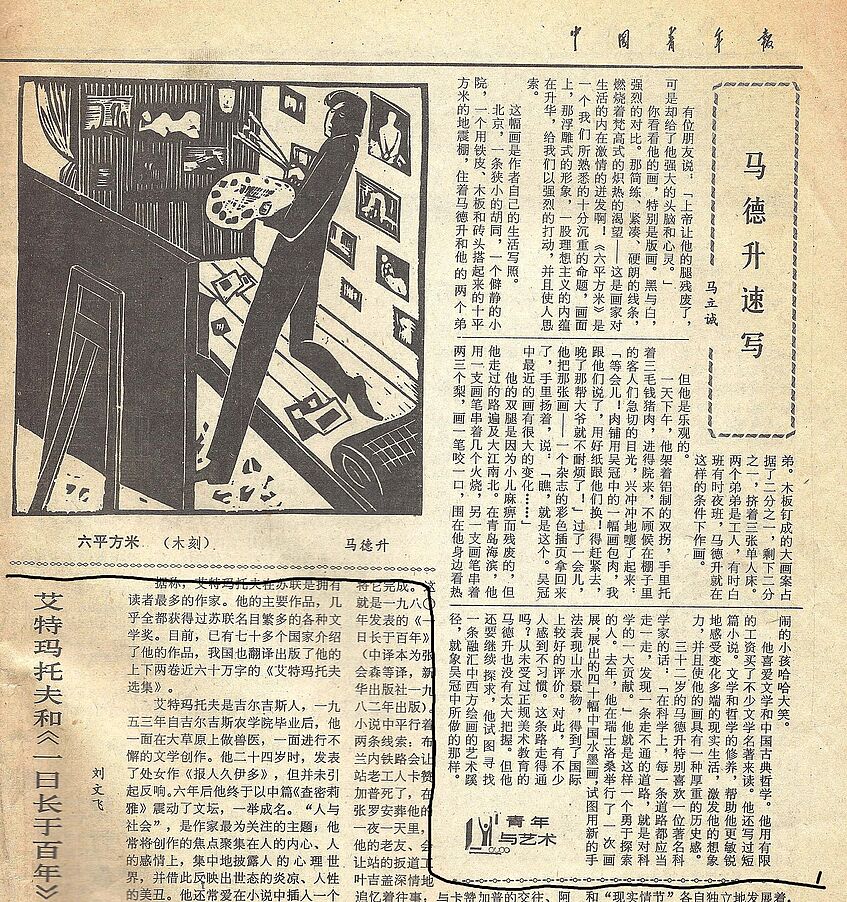

There has been some reporting though on the independent avant-garde art and literary movement, not so much in the daily press, but in some more extensive articles in the fine arts magazine "Meishu" and in some other journals. The focus there is on the new artistic and literary tendencies, omitting all political contexts such as their links with the Beijing Spring movement or the famous street march demanding political and artistic freedoms together with the dissidents on October 1, 1979.

Brochure presenting the "Stars" Group (Changsha)

Article presenting Ma Desheng in the "Chinese Youth Daily" (22.11.1984, p.4)

All this is also true for books and scientific publications on contemporary history or arts. During the 1980s we do find some reporting on the new literary tendencies emerging from the independent journal "Jintian" (Today). Every now and then we find articles on avant-garde artists like Ma Desheng, Huang Rui or Wang Keping. again omitting any political context. There has even been one book (or rather a small brochure) published on the "Stars" artists (Yi Dan: Xingxing lishi [The History of the Stars]. Changsha 2002) in a Hunan publishing house, otherwise the group is usually mentioned briefly in art anthologies.

Original version of the study on the electoral campaign printed in 1980 in limited numbers at Peking University

The Hong Kong publication from 1990

As early as 1981 some researchers at the History Department of Peking University tried to publish a collection of materials and a comprehensive account of the 1980 pluralist elections, but this was quickly discouraged by the university's authorities. What remained was an "internal" brochure printed only in limited numbers. Hu Ping and Wang Juntao, the two successful candidates at the election, had this account published in 1990 in Hong Kong under the title "Kaituo - Bei Da Xue Yun Wen Xian" (Preparing the ground – contributing to the students‘ movement at Peking University).

"The Seventies" (Hong Kong edition from the "Oxford University Press")

Similar pages on street protests are missing from the Beijing version by "Sanlian Shudian", obviously cencored by the authorities.

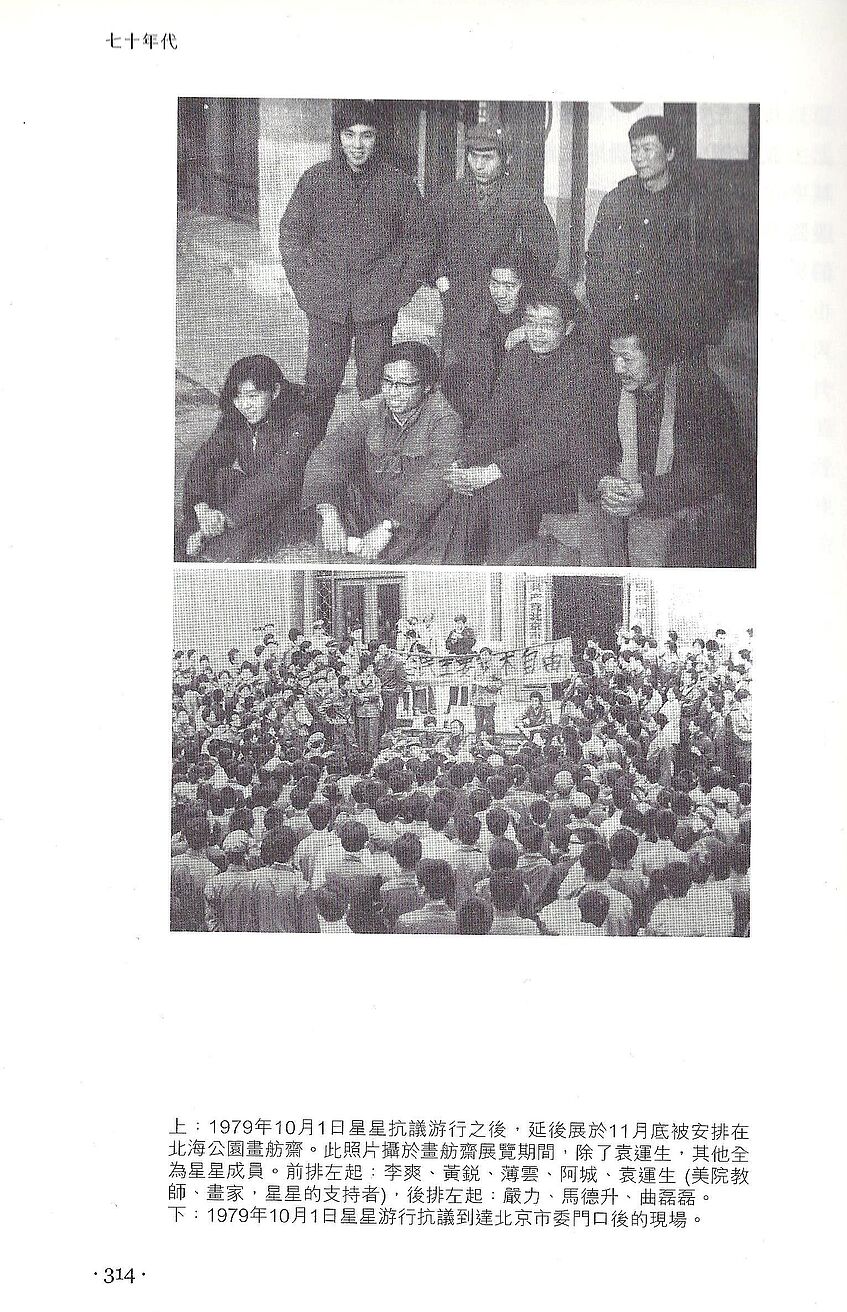

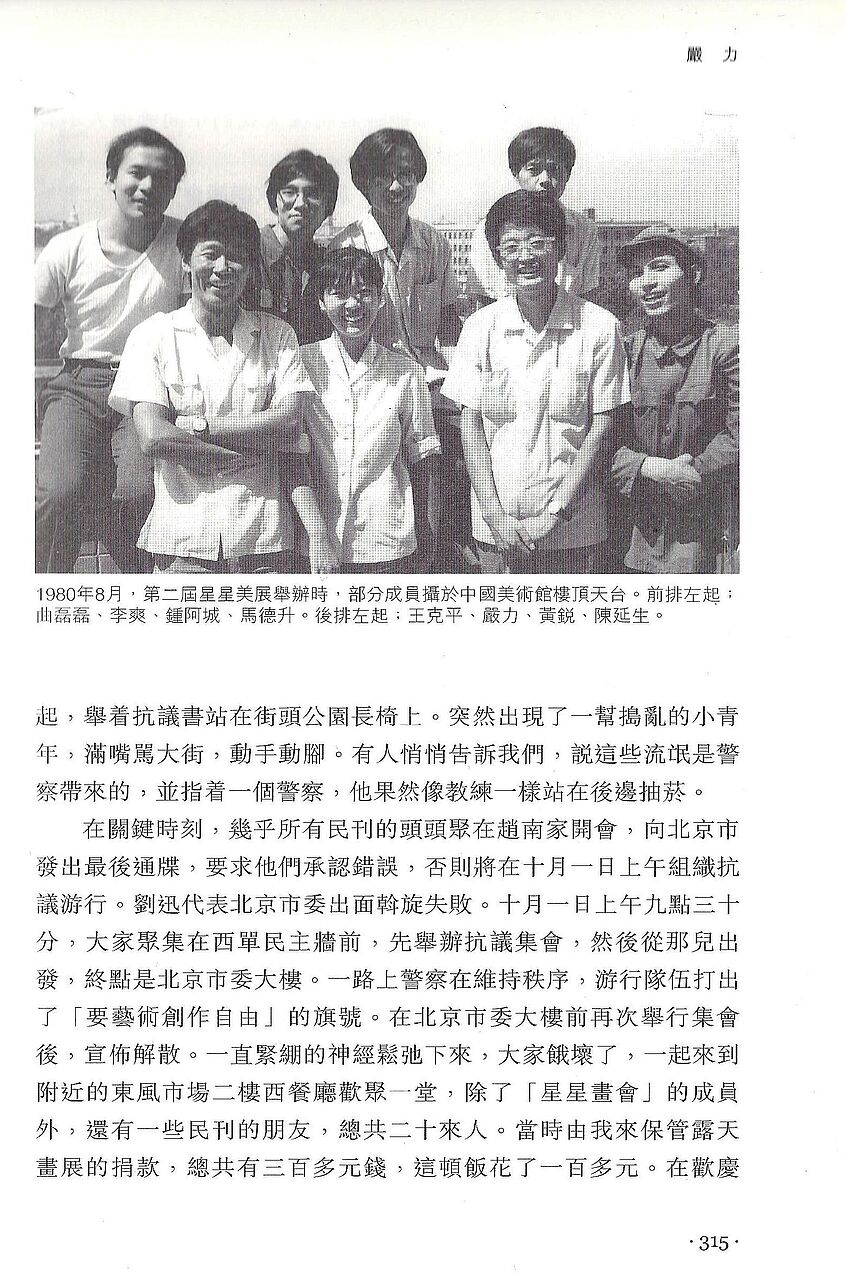

After the year 2000 it still remains difficult (or close to impossible) in China to do academic research or publish comprehensive studies on the political movements of the Beijing Spring. A book on memories of the 1970s published by the "Sanlian Shudian" publishing house in Beijing in 2008 could serve as an illustrative example for this: An article by the "Stars" artist Yan Li is only printed in an obviously censored version, as can be seen from a parallel Hong Kong edition of the same book (from Oxford University Press) that contains extensive descriptions and several photos of the famous October 1 street march in 1979. These pages are completely omitted in the Beijing version.

"The Era Deng Xiaoping" by Yang Jisheng. One subchapter describes Beijing's Democracy Wall.

Nevertheless, there have been attemps by Chinese academics to do some research and documentation of the Beijing Spring, but usually the Democracy Movement gets only briefly mentioned. Even in more comprehensive studies of contemporary history of the 1970s and 1980s, this aspect often is not touched upon at all.

The well-known historian and journalist Yang Jisheng (杨继绳) in his Chinese languange oeuvre "The era of Deng Xiaoping" (Zhongyang Bianyi Chubanshe, Beijing 1998) describes over six pages in rather factual language the big-character posters, the Xidan Democracy Wall, the independent journals and the criticism of Mao. In a personal conversation with the author he pointed out though that this chapter had to be greatly reduced in later printings of the book.

Another book published in one of the official party history publishing houses analyzes the big changes after Mao's death (Cheng Zhongyuan, Li Zhenghua, Wang Yuxiang: Dramatic Years: China 1976-1981. Central Documents Publishing House. Beijing 2008). In a rather critical tone it also describes the dazibao movement of 1978-79, but it does mention the demands for more democracy and the challenges to the communist one party rule, telling also that the movement gained substantial support outside Beijing, and that some high-ranking party cadres sympathized with it.

An "official" assessment of the "Beijing Spring"

Many details mentioned in this book have probably been taken from various internal reports accessible to the authors. The quotes here refer to the 2008 edition (pp. 292-297), names and some paragraphs missing there, have been added in square brackets and refer to a more extensive version of the book (its publishing details still need to be confirmed). These are the main text passages describing the Democracy Movement:

[According to incomplete statistics] more the 80 groups organized themselves in the cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Guizhou, Wuhan and Guangzhou, and some among them were controlled and directed by dubious persons. Using catchwords like "democracy", "freedom" or "human rights", such groups organized by bad elements staged meetings and demonstrations, they posted slogans and dazibaos, distributed leaflets, printed journals, disseminated manifestos and schemes, and put forward various demands. Their actions violated the constitution and other laws, they opposed the leading role of the Communist Party and the socialist system, endangered state security and harmed the interests of the people.

The Xidan Democracy Wall that had sprung up in Beijing from October 1978, became the basis of their propagandistic activities.

When China and the US established diplomatic relations at the beginning of 1979, a letter to US President Jimmy Carter was posted at the Xidan Democracy Wall, using the pseudonym "A young Chinese worker". It glorified the West, dragging China through the mire. The letter asked President Carter for support for a trip to the US [saying "I want to see with my own eyes how your country was able to create such prosperity", adding "because there have not been any positive examples for our lives, all the beautiful things can be stifled."]

On January 6, 1979, Ren Wanding together with six other persons, distributed a manually produced leaflet that carried the title "Chinese Human Rights Manifesto" announcing the foundation of a "Chinese Alliance for Human Rights". He personally handed this program consisting of 12 points to foreign reporters and openly prompted them to interfere with China's internal affairs, saying things like "our Alliance is asking human rights organizations and the general public of the whole world to support us", while the US president was requested to "look after" human rights in China.

In Beijing there was a female worker who together with some campaigners set up a "Citizens' Organization of Petitioners". Supported by several groups, they held a street demonstration at Tiananmen Square, carrying a banner that said "Down with hunger, down with repression, we want human rights, we want democracy". Among several thousand onlookers they marched towards the Xinhua Gate [translator's note: entrance to part of the former Imperial City that now serves as the headquarters for the Communist Party of China and the government] to hand over their demands. They interrupted traffic for more than an hour. When the Beijing City Government ordered the arrest of the female worker on January 18, the "Chinese Alliance for Human Rights", together with six other groups and publications, issued a "Joint Declaration" and planned a protest meeting at the Xidan Democracy Wall before marching to the Zhongnanhai [translator's note: government district in the Imperial City] to hand their demands.

There were not only more and more big-character posters at the Xidan Democracy Wall, but there also appeared some mimeographed publications such as "Exploration" (Tansuo), the "April 5th Forum", "Science-Democracy-Legality" and others. Until April the number of privately published journals rose to more than twenty, posters and journals also leaked classified information, with Wei Jingsheng and his journal "Exploration" giving a typical example.

Wei Jingsheng was a worker with the Beijing Parks Administration, and he became chief editor of the mimeographed journal "Exploration". Writing and distributing articles between December 1978 and March 1979, he agitated to overthrow the government, the dictatorship of the proletariat and the socialist system. He slandered Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought as "a medicine even more efficient than that of a quack doctor", he attacked our dictatorship of the proletariat as "a feudalistic autocracy in the cloak of socialism", and he instigated people "not to trust the dictators' slogan of 'unity and stability' any more", "to direct their anger against the criminal regime that had led the people into this miserable situation" and prompting them "to wrench the power from the old men", meaning the legal government that had been put in place by the Fifth National People's Congress. Wei's article was posted at the Xidan Wall and printed in the journal "Exploration" that was circulated also in Beijing, Tianjin and Guangzhou. Representatives of "Exploration" and other groups also tried in various ways to establish contacts with foreigners in order to gain support for their goals. Whenever they put up a new dazibao, they informed foreigners by phone so that they could come and read the posters. On the fourth day of China's "Defensive Counterattack against Vietnam" [in February 1979], Wei Jingsheng also passed some military information to foreigners.

There also were eight workers from Guiyang, who had come to Beijing to announce the formation of an "Enlightenment Society". Its head office was in Guiyang, with a branch in Beijing, eventually more than thirty people participated. They made every endeavor to propagate so-called "democracy", "freedom" and "human rights" as seen by the capitalist societies. They often met with foreign journalists and wrote - in the form of a dazibao - to US President Jimmy Carter who they called a "savior", asking for a "visit" to the US. In March some leaders of the Beijing "Enlightenment Society" founded a "Thaw Society". In their own manifesto they argued that the dictatorship of the proletariat was dividing mankind, and that "class struggle, violent revolutions and dictatorships of any kind had to be abolished."

In Guangzhou the main section of Beijing Road became a place for big-character posters and mimeographed publications. The journal "Voice of the People" carried commentaries against the Communist Party and Chairman Mao such as "let us not be afraid to be torn into pieces if we dare to bring down the Communist Party off its high horse."

Wuhan also had its "democracy wall", later also a "April 5th Study Group" imitating similar institutions in Beijing.

In Shanghai there was a so-called "Democracy Study Group" that also carried the name "Revival Society". Some of its members called Chairman Mao "a Hitler worse than Hitler," and they put up a huge banner that insulted Chairman Mao; they preached that "the dictatorship of the proletariat is the root of all evil," and they demanded "determined and permanent criticism of the Communist Party," holding that capitalism were better than socialism, and therefore the Four Modernizations would not have priority. It were more important to implement what they called "social reforms", meaning nothing else than becoming capitalistic. ... Some of them had the intention of obtaining "political asylum" abroad, and a few even secretly contacted Chiang Kai-sheks spy organization that was planning sabotage activities.

Another group in Shanghai called itself "Society for the Promotion Of Socialist Democracy", scolding that "the Communist Party had no authority any more," that "people wished the overthrow of the Communist Party," that there was a need for a new system" and "that China should be ruled in a capitalist way." At the same time they said "that it was necessary to drive a wedge between government and people in order to destroy the social/socialist system once and for all."

The Beijing journal "Spring and Autumn Annals" (Yanhuang Chunqiu 炎黄春秋) which used to be close to the Communist Party's reform faction, also published occasional articles on the early era of reform debates and the role that some well-known politicians and party officials (like Hu Yaobang, Zhao Ziyang or Hu Jiwei, then chief editor of the "People's Daily") played in it. In 2016 though, the CCP Propaganda Department took a tighter rein on the magazine, partly because some of its articles on contemporary Chinese history were not always in line with prevalent official views. "Spring and Autumn Annals" was then continued by a new editorial board and a different focus with regard to contents.

Mainland authors writing on the Democracy Movement, usually are only able to publish their books in Hong Kong or Taiwan. They are not available in the People's Republic of China, und Beijing's customs authorities regularly confiscate such publications.

An important researcher from the mainland was the former activist Chen Ziming who unfortunately died at an early age in 2015. He has put together documents and memories of the 1976 Tiananmen Movement and published (in Hong Kong) two extensive volumes on the 1980 election campaigns: "Xianzheng de mengya. 1980 nian jingxuan yundong" (Emerging constitutionalism. The election campaign of 1980, Hong Kong 2013).

Another important book published in Hong Kong in 2010 was edited by Li Zhengtian on the history of the Li Yizhe Group in Guangzhou (The Quest for Democracy/Li Yizhe shijian. Wenge zhong yichang cong xia er shang de minzhu yu fazhi de suqiu/The case of Li Yizhe. A grass-root demand for democracy and legality during the Cultural revolution).

And the historian Yin Hongbiao from Peking University has analyzed political ideas and intellectual trends among Chinese youth during and after the Cultural revolution. His book "Shizongzhe de zuji. Wenhua Da Geming qijian de qingnian sichao" (Footprints of the missing ones. Ideas from the youth during the Great Cultural Revolution) could only be printed in Hong Kong in 2009. Research on contemporary history relating directly to China's democracy movements of the 70s and 80s were not welcome at his university.

Chen Ziming's publication on the 1980 election campaigns

"The case of Li Yizhe" (Hong Kong, edited by Li Zhengtian)

Yin Hongbiao's research on the history of political ideas among Chinese youth up to 1976 (published in Hong Kong)

The only field open to some academic (and private) research inside mainland China have been the developments in avant-garde art and literature from that time. The artist Huang Rui (among some others) has systematically collected material on the "Stars" group. In 2015 (?) he and his friends staged a retrospective on the "Stars" exhibition 35 years before in a private museum near the "798" art district in the outskirts of Beijing, showing not only works of art from that time, but also original copies of the "Jintian" (Today) magazine, photos and documentary film scenes from 1979 and 1980, including some controversial political activities.