Wang Xizhe

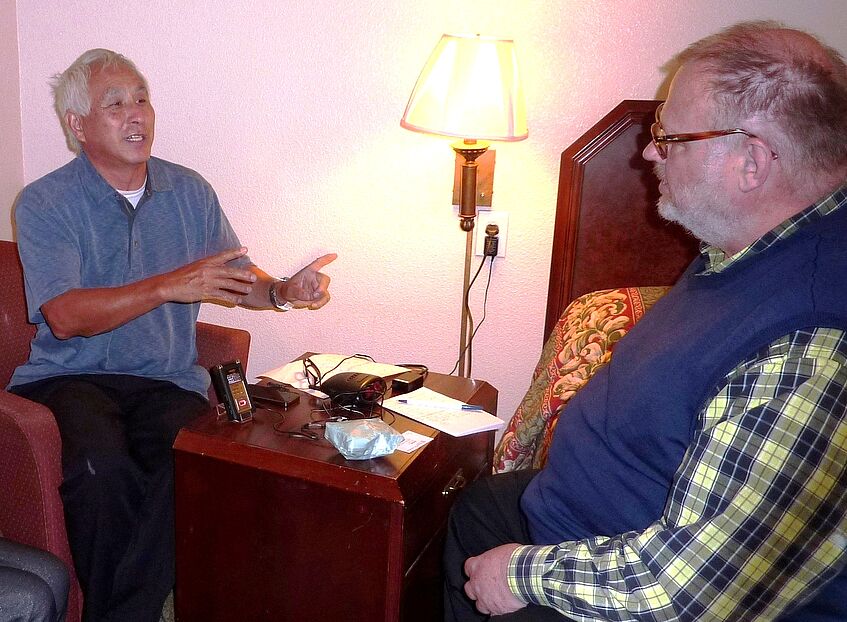

Wang Xizhe at the interview in 2014

Wang Xizhe

... was born in 1948 in Sichuan Province. During the Cultural Revolution he organized a "rebel faction" in Guangzhou which led to his first arrest in 1968.

Together with Li Zhengtian and Chen Yiyang, Wang Xizhe wrote in 1974 - under the pseudonym Li Yizhe, composed of parts of the three names - the manifesto "On Democracy and Legality under Socialism" that was officially criticized, but made the authors well-known all over the country. In 1977 Wang was, like other members of the group, arrested again, but released and formally rehabilitated in January 1979.

Wang immediately joined the "Beijing Spring" Democracy Movement, edited an independent journal in Guangzhou and participated in 1980 in the Ganjiakou Conference where he discussed with Xu Wenli and others the formal foundation of an opposition party. Wang was arrested in April 1980 and eventually sentenced to a 14 years prison term for "counter-revolutionary subversion".

In 1997, he managed to leave China for the US, where he settled in the San Francisco Bay Area. In exile Wang Xizhe participated in various groups and activities, but others criticized his "leftist" positions and certain positive remarks by him on Mao, violence in the Cultural Revolution or the deposed former Chongqing Mayor and "Neo-Maoist" Bo Xilai. Wang defines himself as a "Social Democrat" who opposes today's Chinese Communist Party because of its corruption and "capitalist" politics.

Interview with Wang Xizhe (on June 12, 2014, in a hotel in Berkley, California)

Here you find the Chinese text of the interview.

Wang Xizhe: First of all I would like to say that all what I will be telling represents the evolution of my own thinking. During the Cultural Revolution, we were all still young middle school pupils with relatively simple ideas. The education we received was following the path of socialism. We believed that socialism was the best system in the world, a system that benefited the working people. At the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, the Communist Party and Mao Zedong opposed China's taking the capitalist road because it would make China fall behind and make the working people being exploited again. As youngsters, we rose up to respond to Mao Zedong's call and carried out this so-called Cultural Revolution. We were called “rebels” at that time, including also Li Zhengtian and Chen Yiyang [two other core members of the Li Yizhe Group]. Our organization was called "Red Flag". In middle school we called ourselves the "Jinggangshan Commune". My wife was also a member at that time.

What we realized in this process was that the Communist Party supported us at first, but when we became more radical, we were suppressed and even attacked by the Party. So during this process, we developed some ideological thinking, asking if it was right what we were doing. What was our aim, our direction? So in 1968, when Mao Zedong went on a fact-finding tour around the country, the Cultural Revolution had cooled down a bit, but the ideas our middle school students began to become more vigorous. At the beginning our ideas were quite simple, but later we deliberated in a broader sense. The Cultural Revolution had come to that stage. Mao Zedong called for the Cultural Revolution to be “carried out to the end”. But what was this "end"? Where was it? What was the final rationale of the Cultural Revolution?

Various ideological trends had actually emerged across the country. You may have also heard of the most famous analysis, Yang Xiguang's "Whither China?" [In 1968, he was arrested for posting this text and sentenced to ten years in prison. ] Yang was considered one of the more extreme “rebels” at that time. He believed that the entire Communist Party bureaucracy should be overthrown and new state institutions established. But we found this impossible and not in line with the ideas of Mao who wanted to retain the unified system of the Communist Party. In reality, it still was a bureaucratic leadership of the Communist Party; he just wanted to improve it a bit.

Then there was another ideological tendency at that time, called the "April 14" of Tsinghua University [a breakaway rebel group founded on April 14, 1967]. They believed that after the Cultural Revolution would have brought down the Communist Party's bureaucracy, it would eventually itself become a bureaucratic system. So it was one idea to the left and one to the right. I was influenced by both these two ideological tendencies. Later, when we were sent to the countryside, we experienced the real situation in rural China and in the factories, and we realized that some ideas of the Cultural Revolution were ultra-left and extreme. Thus we began to think that we needed to criticize the emphasis on socialism and the opposition to capitalism imposed during the Cultural Revolution, which forced people to cut off the so-called “tail of capitalism” [remnants of a capitalist economy]. This had caused economic stagnation and backwardness in China and extreme economic deficiency. So we felt at that time that we had to rectify the ultra-left aspects of the Cultural Revolution. But how to do this became a problem as the ultra-left Cultural Revolution leadership, Mao’s ultra-left people, was dominating the ideological field in China. So in order to disseminate our own ideas, we had to fight for freedom of speech first.

At that time, Mao Zedong called upon his followers to go against the mainstream and to dare to speak out, without fear of imprisonment or losing one’s head. I was not afraid of prison or being executed, but still we needed proper conditions to speak out. The first condition was freedom of expression. Not only freedom of speech, but also the "Big Four" for every Chinese (“speak out freely, fully airing one’s views, writing big-character posters and holding great debates”) should always be in the hands of the people and never taken away. But they were finally taken away by Deng Xiaoping who said that he wanted to abolish the "Big Four". But in Mao's era, everything was abolished. He would give it to you when he needed you, and withdraw it when he didn't need you anymore.

At that time, we suggested that free communication, free speech, and freedom of publication, which were already relatively free during the Cultural Revolution, should be continued forever. But wouldn’t that create a completely rampant freedom? I thought we should use a socialist legal system to regulate it. From this perspective, we had the idea of something like a socialist democracy and legality. In fact, we did not know then that in 1957, the Chinese “rightists” had already put forward the same slogan. We discovered it entirely on our own based on the current situation, and felt that China should follow the path of democracy and rule of law. We were not against socialism, but we believed that socialism should be perfected because it lacked democracy. And we basically held the political position that the system of relative stability for the Chinese society represented by Zhou Enlai was in line with the wishes of the of average people. So we basically stood with Zhou Enlai and criticized the Cultural Revolution leaders. This was reflected in the so-called reactionary big-character poster and reactionary ideological trend [the famous Li Yizhe manifesto "On Democracy and Legality under Socialism" in 1974]. At that time, Zhao Ziyang was in power in Guangdong, but he had to implement the orders from the Cultural Revolution leaders and Mao to criticize us. He himself was part of these bureaucratic ranks, and therefore also very contradictory. He wanted to criticize us and protect us at the same time. This was Zhao’s situation. So during the suppression of the Li Yizhe Group, millions of people were mobilized to criticize us.

Interviewer (Helmut Opletal): When Mao found out about the Li Yizhe big-character poster in 1974, do you know if he expressed any opinion on it?

Wang: Yes, he did. According to some statement by the Guangdong Propaganda Department, Mao Zedong had read our manifesto. It did not say that he had opposed us. In his instructions he sent to the Cultural Revolution Committee, he asked whether it could be criticized. It was passed to Ji Dengkui and Li Xiannian [prominent Politburo members] who were in charge then. They directly gave instructions to criticize us.

Interviewer: How were you criticized?

Wang: The mobilized the “masses” in Guangdong province to condemn our dissident ideology. It was Zhao Ziyang [the Party Secretary of the province] who organized big meetings of criticism. But his approach was not to arrest us and allow us to post dazibao to counter the criticism. This made a big impression. Guangdong is adjacent to Hong Kong, and therefore they also got to know about these developments. Even in Taiwan they noticed them. The "Central Daily News" published the full text of our manifesto. A party secretary at that time showed me Taiwan’s Central Daily News adding, “Your stuff has been published in Taiwan. It shows that it is reactionary.”

Interviewer: Did any institution in Guangdong publish an article criticizing your big-character poster, including the text of your manifesto together with such criticism?

Wang: Yes, they didn’t publish such an article. The Guangdong Party Committee had organized a team that used the pseudonym "Xuan Ji Wen" [“collective propaganda article”], written by the Propaganda Department and criticized us at length. We launched a counter-criticism, and they in turn criticized us again. It was very heated. Something like this had never happened since the founding of the Communist Party. There have been opinions from an opposition, but there has never been a formal mutual criticism exchange between officials and the public.

Interviewer: Didn’t many people more than ever get to know your views through this criticism and counter-criticism?

Wang: Oh yes, our slogan was "Democracy and the Rule of Law." At the end of the Cultural Revolution, everyone wanted democracy and rule of law. Both were needed. The legal system to ensure social stability, social and economic development, and prevent people from being in terrorized all day long; democracy to give hope that we enjoyed the right to speak out and express opinions. Our slogan indeed moved the right people. So later, when Hu Yaobang came to power, he made democracy and legal system a national policy. Many people said that it was something that Li Yizhe had proposed. And indeed that can be said to a large extent. Even during the Tian’anmen events in 1989, when Zhao Ziyang was the prime minister [in fact, General Secretary of the Party; the prime minister at that time was Li Peng,] he proposed to solve problems by staying on the track of democracy and legality. We thought he was just using our ideas to solve the problems.

Having said that, I would like to be honest and point out that this idea did not come from Li Zhengtian, but it was Yang Xiguang's concept at that time. Yang Xiguang [the “rebel” author of “Whither China?”] belonged to a relatively leftist group and had not turned to the right. [“Left” in the Cultural Revolution terminology meant more nationalization and centralization, “right” meant allowing more individual freedoms and market mechanisms in economy.] The Li Yizhe big-character poster was rather turned to the right at that time. That was mainly due to me and Chen Yiyang. We had quite vigorous ideas then. The Provincial Committee considered him a college student [referring to Li Zhengtian, who was studying arts], I was a worker, so the attacks were mainly directed against him. Although we were also attacked, the focus was on him. But to be honest, this big-character poster really had nothing to do with Li Zhengtian. Not only did he not write anything, also the ideas were not his. Later it became clearer that he had not participated in the development of these ideas.

At that time, there was also Guo Hongzhi [a fourth core member of the group who preferred to remain in the background] who was considered a veteran cadre. At that time he was younger than I am now, in his forties or fifties. We were in our twenties. He provided us with a lot of information about the internal struggles within the party, which we didn't know much about. This was the background of the Li Yizhe big-character poster. This manifesto did really have a great impact, in the way that although we did not get arrested immediately after, our ideas were widely disseminated. The basic demands were democracy and the rule of law, and we asked people to stand on Zhou Enlai's side which later turned into the "April 5th Movement" [of 1976.] Participants of this movement remarked that they had been largely influenced by us, when this first "Tian’anmen Incident" supported Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping.

Interviewer: Was it the beginning of the rebellion against Mao?

Wang: It was a premonition of an anti-Mao trend.

Interviewer: Another question: The language you used in your big-character posters at that time still contained many communist and Marxist slogans. Some things you are not saying directly but just alluding. So did you want to improve socialism at that time, or did you ultimately oppose socialism? Were you against Mao Zedong? You were of course criticizing Lin Biao, the feudal bureaucratic system, and autocracy. Did you in effect want to criticize Mao through this? On was this not yet on your mind?

Wang: I did not want to oppose Mao Zedong politically. I just wanted to institutionalize a broad people's democracy as it had also been proposed by Mao. For example, during the Cultural Revolution we had the right to publish small newspapers; we had a right to speak, and the right to communicate. By the end of the Cultural Revolution, these were all gone. But we wanted to have them institutionalized.

Interviewer: Were you aware of this during your own debates then?

Wang: At that point, it was indeed not a rebellion against Mao. Only later it was said that we were anti-Mao, it was a label attached to us. But we were not. The most serious thing we said at that time concerned a very important slogan of the Cultural Revolution, "Whoever opposes Chairman Mao will be defeated." We were against this slogan which we considered wrong. We thought there could be various situations in opposing Mao and his theories, some hostile, some non-hostile, and some would just be different views. Mao has certainly made mistakes, so if you criticize or correct him, it does not mean you are against him. Therefore, we concluded that "Whoever opposes Chairman Mao will be defeated" was a principle of feudal ethics. This was our most frightening sentence at the time, and also considered our most “reactionary”. In fact, we did not want to oppose Mao, but still hoped to perfect socialism. Because of this, we were not arrested during the Zhao Ziyang period [1974-1975]. However, after Wei Guoqing was transferred from Guangxi to Guangdong [to succeed Zhao as provincial leader], he had us arrested and imprisoned for two years.

Interviewer: When Mao Zedong had passed away and the Gang of Four collapsed, why did they still keep you detained? Shouldn’t you have been released?

Wang: This was due to the complexity of the Li Yizhe manifesto. On the one hand, it was opposing leftist policies, opposing the Cultural Revolution leaders, and it criticized Mao. So logically speaking, we should have been released. But the members of the Li Yizhe Group came from the “rebels” [leftist factions of the Red Guards], so those who kept us in prison, still felt threatened by us, thinking that we were “rebels” after all, and we tried to please both sides. So Wei Guoqing and his people arrested us because they considered us Cultural Revolution “rebels” and reactionaries. But when leaders like Hu Yaobang and Deng Xiaoping came up, they understood better. Although we were “rebels”, our main focus was to support them and target the leaders of the Cultural Revolution. Then Xi Zhongxun [Xi Jinping’s father; a leading politician persecuted during under Mao and rehabilitated in 1978] was transferred to Guangdong province, and he exonerated us. Xi Zhongxun came to see us in person many times, and I had a very good impression of him. He was a good man.

But some people say that Xi Zhongxun might have also turned against Mao after having been persecuted by Mao for so long, even his son Xi Jinping. But I don’t think so. In my contacts with Xi Zhongxun, he still showed great respect for Mao. He was condemning precisely those of us who had criticized Mao. We should not completely refute Mao, he said.

After we had been rehabilitated, the Democracy Wall started. So why did I separate from the Li Yizhe Group then? It was because at that time, Guo Hongzhi and Li Zhengtian basically followed Deng Xiaoping's faction. They believed that things were ok now, the problems had been solved, and we had achieved “stability and unity”, a slogan of that time. But this was not my view. Although the reformists of the Communist Party had come to power, Chinese democracy and rule of law had not been established yet as a system. The system of the Democracy Wall should also be implemented, and we should continue to push this movement forward. That’s why I had these differences with them.

Li Zhengtian often spoke badly about me in front of Xi Zhongxun. At that time, I said something rather radical. Before, I still used to criticize the Communist Party from a communist standpoint, but I had already began to dislike the Communist Party. I once said to Chen Yiyang, "From now on, I will break with the Communist Party." This sentence was reported to the Guangdong Provincial Committee by Li Zhengtian. Later on, the Guangdong Party Committee became very suspicious of me and detested me very much. But I didn’t care anymore. I joined the Democracy Wall Movement. Already at the beginning, we were confronted with the issue of Wei Jingsheng, weather should we go to back him. We didn’t like some of Wei Jingsheng’s actions at that time, but I still felt that we should support his liberation. Li Zhengtian and Guo Hongzhi didn’t want to intervene. They were critical of Wei Jingsheng. That’s how we completely separated. From then on, I had basically left the Li Yizhe Group, and I had nothing to do with Li Zhengtian and the others any more. I believe Sasha Gong might have said the same. Sasha Gong was also on Guo Hongzhi's side.

I continued to get involved in the Democracy Wall Movement, and thus became associated with Xu Wenli. Xu was in Beijing, and I participated in his "April 5th Forum", and began to actively participate in the Democracy Movement. First we campaigned for Wei Jingsheng’s release, then for Liu Qing. Around this time, Xu Wenli suggested to form a party for which he proposed the name "League of Communists," a name that he had taken from Tito’s Yugoslavia. It sounded equivalent to a faction within the Communist Party. But I didn't agree with it. I didn't want to form a political organization at that point, but develop some political ideas. So I didn't agree. But even without my consent, the communist spies still made their analysis and said that we were secretly forming a party. That’s why we were arrested again. Wei Jingsheng was arrested first, and then, in 1981, I and Xu Wenli, and Fu Shenqi. They were sentenced to more than ten years, 15 years. I had to stay 14 years in jail, a very long time. When I was released from prison, my ideas began to change. That was in 1993, when the year of 1989 had already passed. I was still in prison on June 4, 1989.

Interviewer: In prison, how did you get to know about the June 4th events outside?

Wang: Before 1988, China’s political prisoners were kept together with ordinary inmates. They had to do very hard labor and were made to suffer even more severely than ordinary criminal prisoners. But after 1988, I don’t know why, the Communist Party pursued a new policy of separating political inmates from criminal prisoners, and they established a small prison inside the prison that was reserved for political prisoners. A number of political prisoners were put there, including Liu Shanqing who had come from Hong Kong to support us at the Democracy Wall. There were about five or six of us.

Interviewer: Were you locked up together?

Wang: No, we were separated. But we could talk to each other by lying down in front of the window. As it was a prison within the prison, the building was not very high. Before 1989, discussions under the Communists were relatively open, even newspapers were quite free.

Interviewer: Could you read newspapers or watch TV?

Wang: Papers I could read, TV I watched only occasionally, so it was mainly newspapers like People's Daily, Southern Daily, and the English language China Daily. I was learning English at that time, but I couldn't learn it well in prison. I wanted a tape recorder, but they refused it to me. I pronounced everything phonetically, so my English was a mess, but I could read some. The China Daily was relatively open. When Hu Yaobang was ousted [in 1987], I knew there was a big problem. The most sensitive episode was the "April 27 Editorial" of 1989 [actually "April 26 Editorial" of the People's Daily with the headline "We must take a clear-cut stand against the unrest".]

The mourning had started the day in April when Hu Yaobang had passed away [April 15]. I was fully familiar with this. At the beginning of a popular movement often – in Mao's words – "the dead are used to put pressure on the living." It meant to fight for certain demands under the guise of a dead party leader. During the Cultural Revolution, this was often the case. The “April 4th” [of 1976] was also in the name of Zhou Enlai. Deng Xiaoping, still alive, was overthrown then.

Interviewer: So you were basically aware of what happened in the June 4th incidents?

Wang: For me, it was very clear that with the events around Hu Yaobang, a new movement was about to start. But my understanding was that like the Cultural Revolution, it was basically a pro-democratic movement within the system. But on April 26, Deng Xiaoping ordered this editorial to be published, calling the events unrest or something like that. Based on past experience, people needed support from within the Party to begin a movement. However, if the Central Committee of the Communist Party published a document saying some doings were wrong, generally speaking, people would not dare to carry on. During the Cultural Revolution, there was something named “a call from the Cultural Revolution leadership”. If that one came and it approved something, then everyone carried on even more actively; but if it opposed it, then people won't do anything anymore. But this time I noticed that although the government had issued such a document on April 26, students still dared to come out to resist on April 27. I thought that this was an epoch-making event that ordinary people dared to resist the central government. The "April 4th Movement" [of 1976] still did not dare to openly oppose the central government, although some radical slogans were heard, such as "The era of Qin Shihuang is gone forever" [the Han emperor was Mao’s idol, such slogan was interpreted to attack Mao] etc., but these were still relatively indirect and they did not dare any direct attacks.

But "April 27" was a truly popular movement directly confronting the central government. It was a bit like the Li Yizhe big-character poster period, when the central government was divided into two factions. The Zhao Ziyang faction was more sympathetic to the students because he was an emerging force and they hoped that he would use the democratic forces to consolidate his position. The other faction was Deng's, some old bureaucrats. They were afraid that this democratic movement would affect their status, so they wanted to suppress it. In this showdown, after the May 4th anniversary [of the 1919 student movement], Zhao Ziyang's faction seemed to have the upper hand. Zhao proposed that problems should be solved on the basis of democracy and the rule of law. At this time, Deng had not yet thought of using military force to solve the problem. He thought that if Zhao Ziyang could deal with it well and solve it, he would let him do.

Interviewer: You knew all this in prison?

Wang: I knew it all. I could read it in the newspapers, and I could draw my conclusions because of my political experience. At this time, I also concluded that Li Zhengtian would not manifest himself at first, but after May 4th, Li Zhengtian could come out supporting Zhao Ziyang. This was later confirmed to me. Li still belonged to the Cultural Revolution faction, and he retreated before the repression by the central government. But this popular movement was different from the Cultural Revolution. During the Cultural Revolution, we always had our commanders. I also was a commander of the Red Guards, and there also was a commanding headquarters. But during the June 4th Movement, there was no command center and the students rose up spontaneously. At the time of the Democracy Wall, some older democracy activists were still in prison. There was no strong core leader, so we didn’t know when to advance or retreat.

After May 4th, Zhao Ziyang had a relatively comfortable situation and sent his representative Yan Mingfu [then Minister of United Front Work] to hold talks with the students, and also Yuan Mu [spokesperson of the State Council]. The students were all affiliated with the "Autonomous Federation of University Students", which meant that they were actually recognized as a non-governmental organization. Had the Communist Party been given a chance to retreat, it would have pushed this movement further forward. But this is always the case in popular movements without a strong leadership. The more radicals are moving to the top, the more this will push the movement into the abyss. I was in prison at that time and was very worried. I saw that Wan Runnan, the general manager of the Stone Group [a leading tech company supporting the students], went to Paris to organize the "Front for Democratic China" after June 4th, with him as the chairman.

In the end, June 4th became a great tragedy when Deng Xiaoping decided to suppress it. Deng Xiaoping's decision actually had its uses, because to suppress it, he did not need hundreds of thousands of soldiers. During the "April 5th" period, Mao Zedong had to mobilize the militia. But during the June 4th, the student movement had already reached a low point and was tired. Mass movements always have a process of climax and fatigue.

If you want to blame someone you still cannot blame the ordinary people. It was only Deng Xiaoping's responsibility. If we put it all together, something definitely had to happen in the end and turn it into a big disaster. After this tragedy, there was a lot of international pressure that helped us. In the past prison life used to be very hard, but after June 4th, it improved. Why? Because the whole world paid attention to China’s political prisoners. In the past, the world had paid little attention to them, but afterwards the treatment has improved. My wife could also bring me something to eat from time to time. Then in 1993, when China wanted to host the Olympics, it made deals with the West. This was the time when they released Wei Jingsheng. But it seems that I was the first one to be released. Then they also liberated Wang Dan, Xu Wenli, and Wang Juntao. Wang Juntao left for the United States.

After my release, I still wanted to push China's democratic cause forward. I was thinking all the time to find a force that could enable this. At that point, I didn't know yet about such pro-democracy movement overseas. After the Democracy Wall, I had been in jail. The overseas movement was initiated by Wang Bingzhang in 1980 [a leading dissident in exile, who was abducted in 2002 from Vietnam and sentenced to life imprisonment in China]. He said that developing the Democracy Movement was a legacy of the Democracy Wall. The pen name he used was "Wang Jingzhe". The character "jing" referred to Wei Jingsheng, and "zhe" to Wang Xizhe. At that time I didn't know this.

I was thinking about Taiwan and the influence of the Kuomintang then. When Deng Xiaoping's power had become stabilized, he wanted to solve the Taiwan issue. One of his slogans was that as long as the One-China Principle was recognized, any issue could be discussed with Taiwan. That seemed easy to handle. As it was not the time of Lee Teng-hui [a Taiwanese nationalist] yet, but still the period of Chiang Ching-kuo [Chiang Kai-shek’s son]. Chiang Ching-kuo had just passed away, but the policies were still those of his period. He had died in 1988. Therefore, the one-China issue was not a problem for Taiwan then.

Since under the One-China Principle, anything could be discussed, we wanted to push the Kuomintang and the Communist Party to talk about a peaceful reunification and democratization of China. That seemed a good lever to me. After the end of the Anti-Japanese War, Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-shek had signed an agreement, the highest-level agreement ever between the Kuomintang and the Communists [on October 10, 1945 – usually shortened to “10.10.” or “Double Tenth“ in China; also Taiwan’s National Day, commemorating the Wuchang Uprising of 1911]. It was negotiated in Chongqing by Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-shek in person and then signed by Zhou Enlai. It basically stipulated that China should be democratized and its military nationalized. In negotiation between the Kuomintang and the Communist Party, I wanted to use the power of this agreement.

Later I discussed this with Liu Xiaobo in Guangzhou. I proposed to issue a "Double Tenth Declaration" calling on the Kuomintang to adopt a positive attitude toward the mainland, to negotiate with the Communist Party, and to go for a democratization of China. But in the end, Liu Xiaobo [he later received the Peace Nobel Price] was arrested and sent to a labor camp. And I ran away. I was still on parole at that time and could be arrested again at any time, so I fled from Shanwei to Hong Kong. Hong Kong did not dare to detain me. They would have soon been asked to return me to China. So they eventually handed me over to the United States. In fact, I had no intention to go to the United States at that time; I just wanted to stay in Hong Kong. At that time, the Political Department of the British Hong Kong authorities, before Hong Kong’ handover to China, just transferred me to the American Consulate. The U.S. Consulate asked me what I wanted to do. I answered, "If Hong Kong can't keep me, I have no choice but to go to the United States."

When I arrived in the United States, I still wanted to use my scheme to solve the question of democratization, so I said I wanted to go to Taiwan. I could join the Kuomintang to promote negotiations between the Kuomintang and the mainland. But it turned out that the timing was bad again because Taiwan had changed. Lee Teng-hui had come to power, and he began to move towards Taiwan independence. Unification with China was not an issue for them; it was one country on each side. Since there already was one country on each side, there was no need to talk about peace and reunification issues with mainland China. So my idea had failed again. I visited many overseas pro-democracy organizations, and many of them supported Taiwan independence because they thought as long as they supported Taiwan independence, they were anti-communist. But they did not think that by supporting Taiwan independence, they would be separated from China's affairs and not be able to use Taiwan to influence the mainland any more.

Moreover, there were many problems in the overseas pro-democracy organizations. There were also corruption and some other issues that I didn't like very much. I became more and more separated from the overseas Democracy Movement. We pondered, since there was no solution to the Taiwan issue in sight, what other kind of power could we turn to? I just wanted to support an opposition political party in China, so I supported a party called "China Democratic Party". Xu Wenli was still in China at that time, and he had started organizing it in 1998. I gave Xu Wenli support from abroad and assisted the Democratic Party operating in Zhejiang.

But later I discovered that the entire overseas Democracy Movement was different from my ideas. I am basically a democrat, but also a nationalist, and I still value the interests of my country and the nation. But overseas people basically only emphasize so-called democracy, but not the interests of the nation, and they do not emphasize patriotism. Wang Bingzhang and I both emphasized this point, and we became more and more distant from them. After Xu Wenli had come out, I handed over all the affairs of the China Democratic Party to him. But as of today, the China Democratic Party led by Xu Wenli still adheres to my original idea and relies on the influence of Taiwan to eventually achieve a pluralistic political setting with a Communist Party and a Kuomintang Party. But for me this seems unlikely because Taiwan is already more or less on its own. I have explored all the different forces, but in the end, to be honest, I had no choice but to return to the Communist Party. You also know that I was not anti-communist at the beginning, nor was I anti-Mao. I just wanted China's democratization. Later I discovered that China's reformists in general had also become corrupt, so there was a problem. I had hoped that the Communist Party itself would split. For using external forces to promote China's democratization, there seems to be little hope. The Democracy Movement itself has no strength, and Taiwan has lost its original enthusiasm. Only the Communist Party could divide into different factions in order to achieve democratization.

Is this path impossible? It is still possible when I look on American democracy. American democracy is the George Washington Revolution, it is Andrew Jackson and the others. [Andrew Jackson, 1761-1845 US President and co- founder of the Democratic Party]. After they had chased the British, they did not split into parties at first. But later, the federalists and localists started to have conflicts. …

Interviewer: You said you were returning to the Communist Party. What do you think of the current political situation in China?

Wang: I have to make it clear first that I have seen the United States going through a process of division, that finally ended in having the current Democratic Party and Republican Party. The revolutionary group of George Washington later separated. So I think that such a revolutionary group within the Communist Party may eventually split off. Why? Precisely, because the traditional forces within the Communist Party did not benefit from the reforms, but still adhere to traditional fundamentalist social justice. The other part is mainly the Deng Xiaoping's group, with Deng and later Zhu Rongji and Jiang Zemin. Their reforms basically turned state-owned units into privatized ones. In this process of privatization, benefits were often appropriated by Communist Party bureaucrats and other influential people who became a new bourgeoisie. That’s why the Communist Party will eventually have to split, and it will definitely split.

What is behind all this? It is a matter of whether or not to support the reformists. In fact, I do not need to support the reformists, nor do I need to oppose the conservatives. Historically, reformers have often been corrupt. Why? Because reformers want to reform the old interest system, and in the process of changing the old interest system, new interests will be generated or discovered. And who will get these benefits? They will definitely be appropriated by the reformists, leading to a new increase of bureaucrats. It is very obvious in China that the reformists now are basically corrupt. They are simply turning corrupt. Starting from Deng Xiaoping’s group, Zhu Rongji’s group, and ending with Wen Jiabao. It has been revealed that Wen Jiabao's family possessed billions of assets. Before 1976, in the eyes of conservatives, common people supported the reformists. But now, to be honest, common people support the conservatives and not the reformists. Because the reformists have gradually become corrupt.

So I think I should promote the struggle between the two factions of the Communist Party so that both factions can be legalized and institutionalized. By such a method and going this road, China could move towards democratization. And if this continues, the inevitable result will be that the top leaders of the Communist Party will be chosen through democratic elections. Since Deng Xiaoping, the Communist Party has already taken a first step. The term system for the top leaders is five years for one term and five years for a second term, it cannot exceed ten years. Thus one problem has been solved. But how should a successor be chosen? Before he could only be designated by Deng Xiaoping. Deng’s designation of Jiang Zemin facilitated Hu Jintao's appointment by Jiang Zemin. [In fact, Wang Xizhe has by mistake mixed up the order of Deng’s successors, it has been corrected for the translation.] Later Hu Jintao designated Xi Jinping. Basically, we are still heading in this direction where leadership issues are gradually solved by inner-party democracy. The Communist Party has been moving step by step towards democracy within the Party, but now it has been interrupted again. So there is still a crisis inside. So which direction should the Democracy Movement take with regard to a democratic reform of the Communist Party? I can only say that for me it seems unlikely that the Democracy Movement can completely overthrow the Communist Party and replace it. In the past, the Democracy Movement could play an important role because China was relatively weak. To reform and open up, China had to rely to a large extent on the support of the West. Therefore, when the West put more pressure on the Communist Party, it became more afraid and made some kind of compromises. Releasing us from jail in 1993 was such a compromise between the Communist Party and the West.

But it has become increasingly difficult for the Party to make compromises. Even Liu Xiaobo, as a Nobel Prize winner, should have been allowed to leave a long time ago, but now they are determined not to let him free. What does this show? It illustrates the balance of power. It is becoming increasingly difficult for the West to put pressure on the Communists, and for them it is increasingly difficult to compromise. The only way now is to promote divisions and splits within the Communist Party. Why do I not really stand with any of the factions or sides of the pro-democracy movement now? Because I stand to promote China as a whole, supporting both the left and the right, and supporting them to express their opinions democratically and freely. I want them to freely form their political groups and their own political forces.

Interviewer: How do you think about the fighting during the Cultural Revolution now?

Wang: The struggles during the Cultural Revolution were actually a beginning of intra-party democratization. In fact, the process of the Cultural Revolution showed that China had started moving towards democracy. But the problem was that it had not been legalized. It still remained a life-and-death struggle between us and the enemy. If I fight you down, I will come up; if you fight me down, you will come up. In a legalized form, both factions of the Communist Party would have put forward their political programs and ideas, and hand them over to the Party and the people of China, allowing them to choose and decide who would come to power through democratic methods. That would have meant moving gradually toward democratization. Therefore I believe that the Cultural Revolution actually was a factional struggle, a repeated exercise in one being promoted to power and another one being removed from it. But the shortcoming was that there was no standardized and democratic way. It should not have been a contradiction between us and the enemy, it should not have been fought as a life-or-death challenge, but be turned into something democratic instead.

Interviewer: Summing things up, could you explain the differences between the Democracy Movement in Guangzhou and that in Beijing?

Wang: In terms of characteristics, this is not a big question, there was no big difference. Because Beijing is the capital, everything involves the central government. Take the issue of Wei Jingsheng: Deng Xiaoping gave the instructions to arrest him. And this directly influenced different opinions within the central government. Guangzhou was farther away from the center, Guangzhou’s influence was not as great as that of Beijing. But in terms of the characteristics of the movement, there was no difference.

Interviewer: Guangzhou is very close to Hong Kong. How did Hong Kong influence you?

Wang: This is true. Hong Kong has greatly supported the 1989 pro-democracy movement. At the very recent commemoration of June 4th, hundreds of thousands of people in Hong Kong took to the streets. Hong Kong's support was also important for our movement in Guangzhou. At the beginning, Hong Kong people did not understand the situation further north. When they made their first steps to Guangzhou, they met me, Liu Guokai, and He Qiu [other activists in Guangzhou]. At the beginning, it was the Trotskyites who were the most active in Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement. In Guangzhou they made contact with us, and we introduced them to northern China. They slowly got to know the pro-democracy movements in Shanghai and Beijing. That’s how they became part of the national movement. When it finally developed into the 1989 Democracy Movement, they provided comprehensive support. From this point of view, Guangzhou was a bridge between the democratic movements in Hong Kong and mainland China.